Columbus: DNA evidence challenges syphilis origin theories

- In the 15th and 16th centuries, Europe was ravaged by the worst-ever outbreak of venereal syphilis. It was the first time the sexually transmitted infection had ever been seen, and it was much worse than the version that still afflicts people today.

- Legendary Italian explorer Christopher Columbus is commonly accused of starting the outbreak. The idea is that members of Columbus' crew brought syphilis back to Europe after an expedition to the Americas in 1493.

- However, recent DNA analyses of ancient remains challenge this tidy tale.

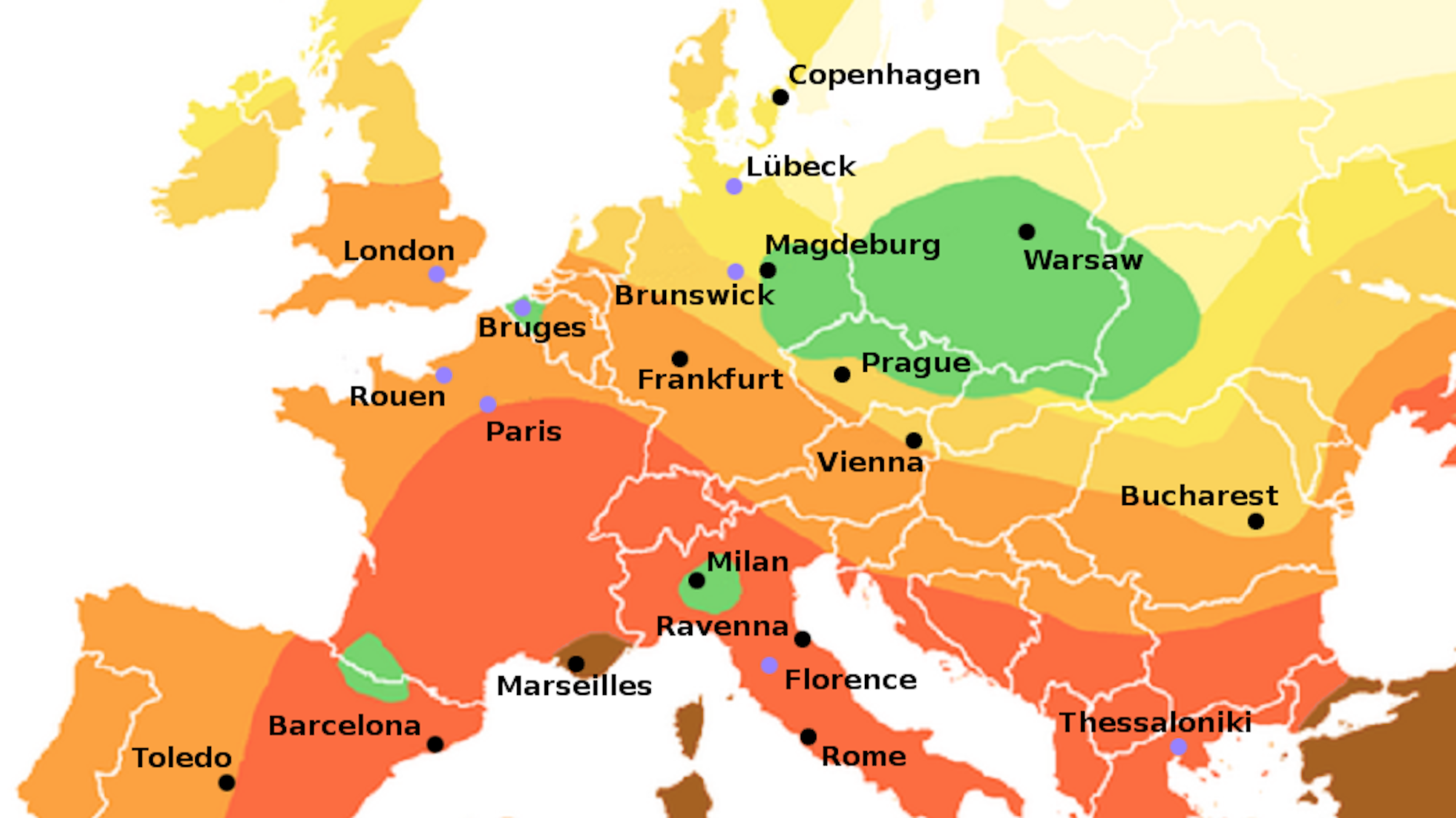

In the summer of 1495, a new plague swept across Europe, one that was horrendous in scope and personal effect. As many as five million Europeans died over the ensuing decades out of a population of roughly 65 million. They met their ends in torment — marred, fevered, wracked by pain. Even those who avoided infection were still scarred by memories of the plight of the afflicted.

Surgeon Marcello Cumano provided the first known description, which medical historian Eugenia Tognotti paraphrased in a 2009 publication:

“The first manifestation of the disease was the appearance of a painless skin ulceration localized on the penis. Sores and pustules then appeared all over the face and the entire body, accompanied by joint pains…”

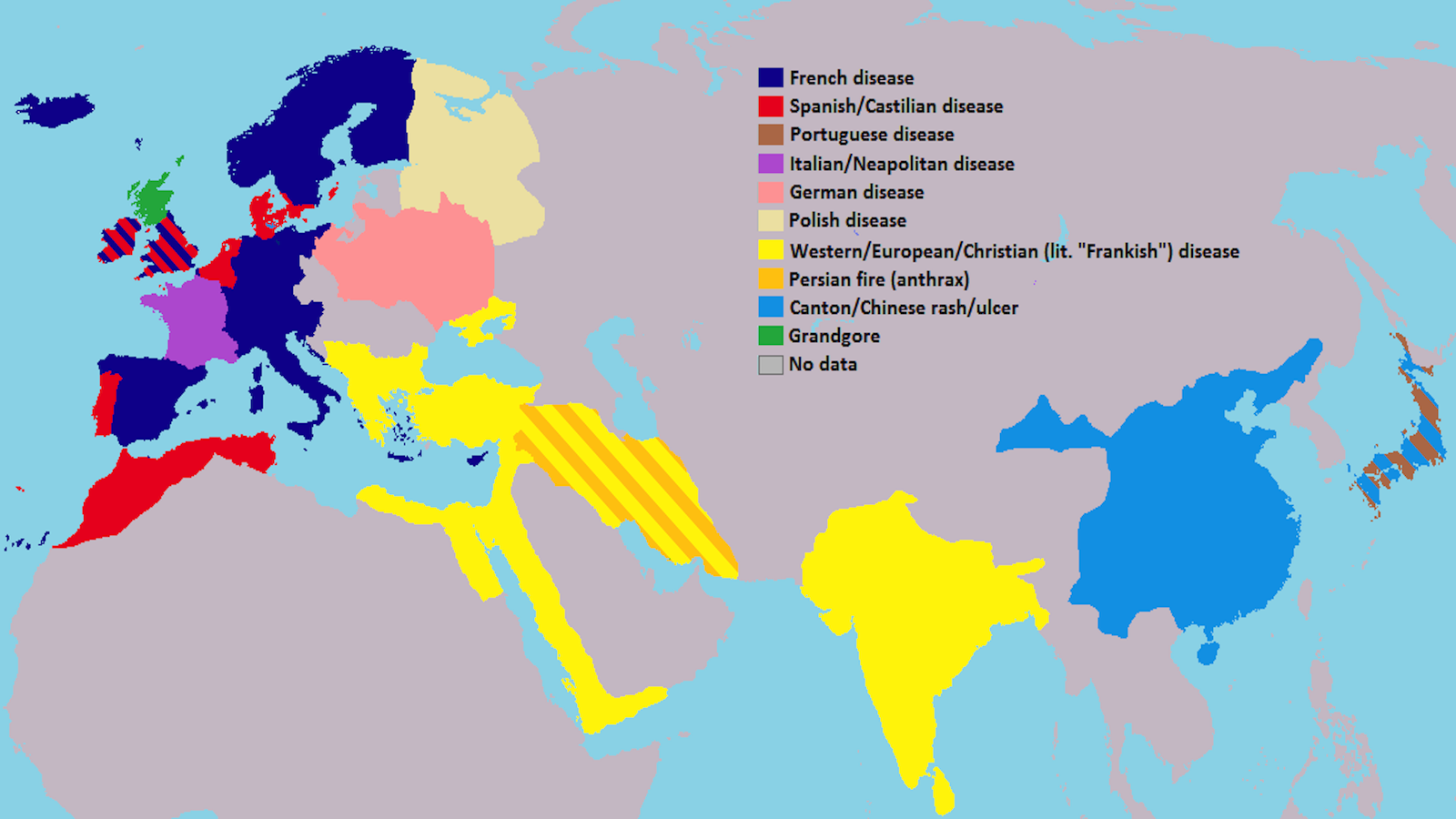

The latter part of the disease, which manifested 40 to 60 days after the appearance of the first ulcer, left sufferers disfigured, scarred, and often dead. As Tognotti noted, contemporaneous descriptions are “unanimous in emphasizing the violent and malignant character” of the ailment. Pustules blanketed patients’ bodies, stinking, oozing, and destroying the underlying tissues. Afflicted individuals “wasted away from boils and pain.” Physicians at the time called the novel illness by various names: “French disease,” “Disease of Naples,” “venereal lues,” “Great Pox,” and “Morbus Gallicus.” Today, we call it venereal syphilis.

“When syphilis first appeared in Europe in 1495, it was an acute and extremely unpleasant disease,” Tognotti wrote. “After only a few years it was less severe than it once was, and it changed over the next 50 years into a milder, chronic disease.”

Scientists now know that syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection, caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum pallidum, which can be effectively treated with a course of antibiotics. What they still don’t know, however, is where exactly it came from.

Tracing the origins of syphilis

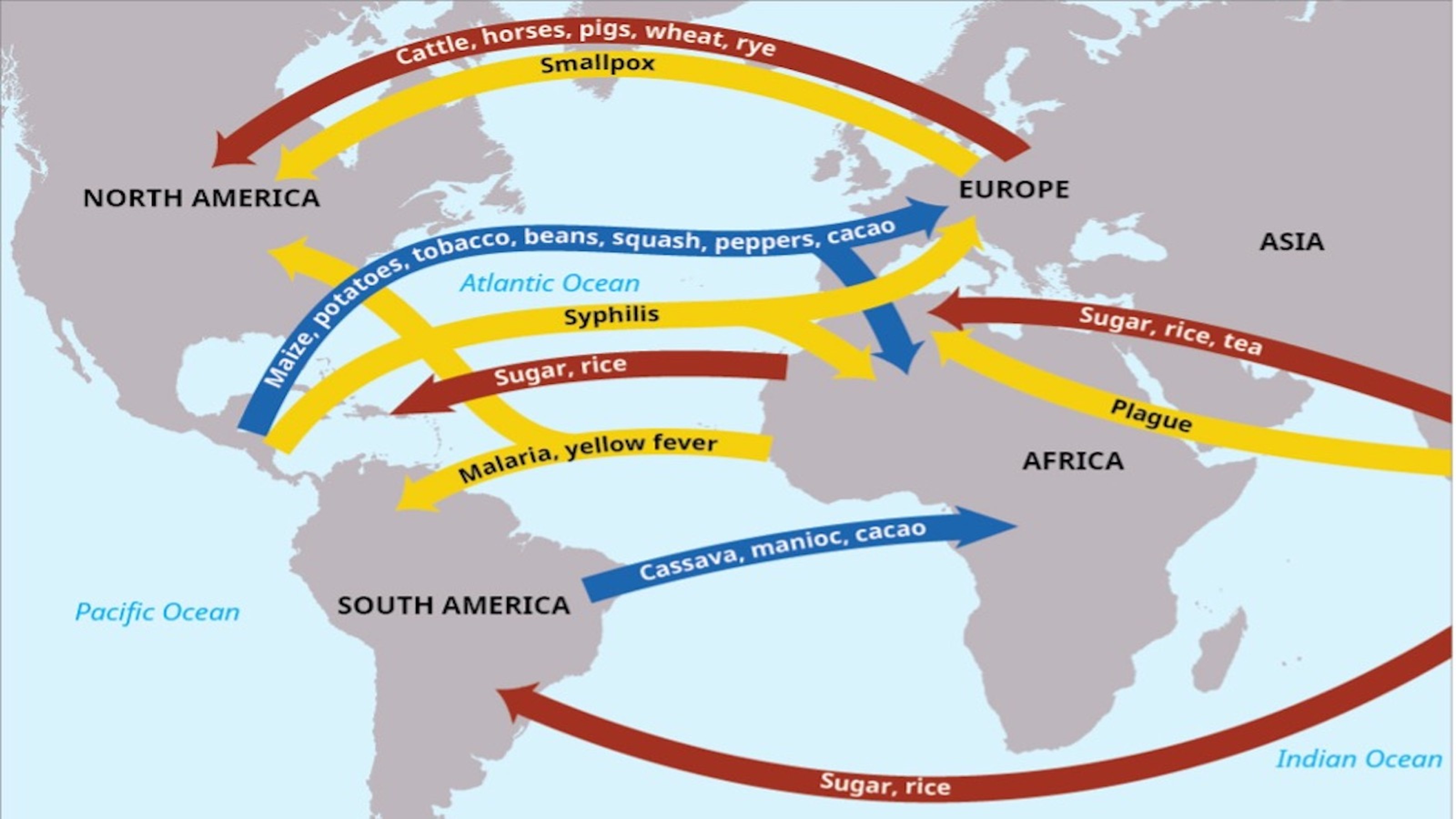

A popular theory involves the legendary and controversial Italian explorer, Christopher Columbus. The idea is that members of Columbus’ crew brought syphilis back to Europe after an expedition to the Americas in 1493. Upon returning to the Old World, some of them may have then joined French King Charles VIII’s mercenary army as it marauded through Italy in 1494 and 1495. The mass of men and arms would have provided fertile ground for syphilis to roil and mutate. Then, when the force disbanded that summer, soldiers returning to homes all across Europe could have seeded the destructive disease across the continent.

It’s a tidy tale, one that scientists have long generally accepted. But today, researchers can scour ancient remains for minute amounts of DNA from pathogens, an ability that’s raised questions about the theory.

A few years ago, when a group from the University of Zurich looked closely at bones found in Finland, Estonia, and the Netherlands dated to before syphilis’ devastating arrival in the late 15th century, they found DNA from subspecies of Treponema pallidum, the bacterium that causes syphilis. This means that while venereal syphilis may not have been present in Europe before the 1495 outbreak, closely related diseases caused by nearly identical bacteria were. According to the authors, one of these pathogens could have easily mutated into the one that causes venereal syphilis. In short: Columbus and his crew could very well be innocent.

A recent study by members of the same University of Zurich team in partnership with researchers at the University of Basel further bolsters the case for acquitting Columbus for the rise of venereal syphilis.

The researchers screened the remains of 99 individuals buried at a 2,000-year-old site on the Brazilian coast for Treponema DNA. From their analysis, they were able to reconstruct four ancient genomes of a prehistoric treponemal pathogen most related to the one that causes bejel, or endemic syphilis. Bejel spreads through skin-to-skin contact and causes skin lesions similar to those seen with venereal syphilis. It also can occasionally deform bones. Though highly unpleasant, bejel is generally not life-threatening.

While the study provides clear evidence that syphilis-like diseases were endemic to the Americas dating back to the 1st century CE, there was no sign of the treponemal pathogen that triggered Europe’s deadly syphilis pandemic centuries later.

“As we have not found any sexually transmitted syphilis in South America, the theory that Columbus brought syphilis to Europe seems to appear more improbable,” corresponding author Professor Verena Schünemann said in a statement.