A brief history of hell

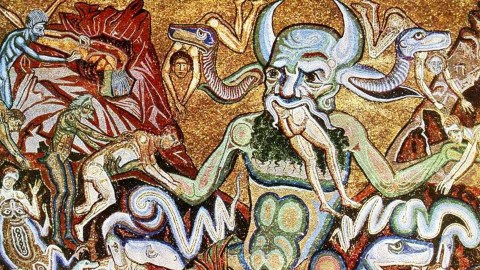

Coppo di Marcovaldo. (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

- Hell is mentioned sparingly in the Bible, with many references being either ambiguous or mistranslations.

- The concept took shape in the 2nd century as the result of cultural exchange in the Mediterranean region.

- Each era since has refashioned hell in its own image, for better and for worse.

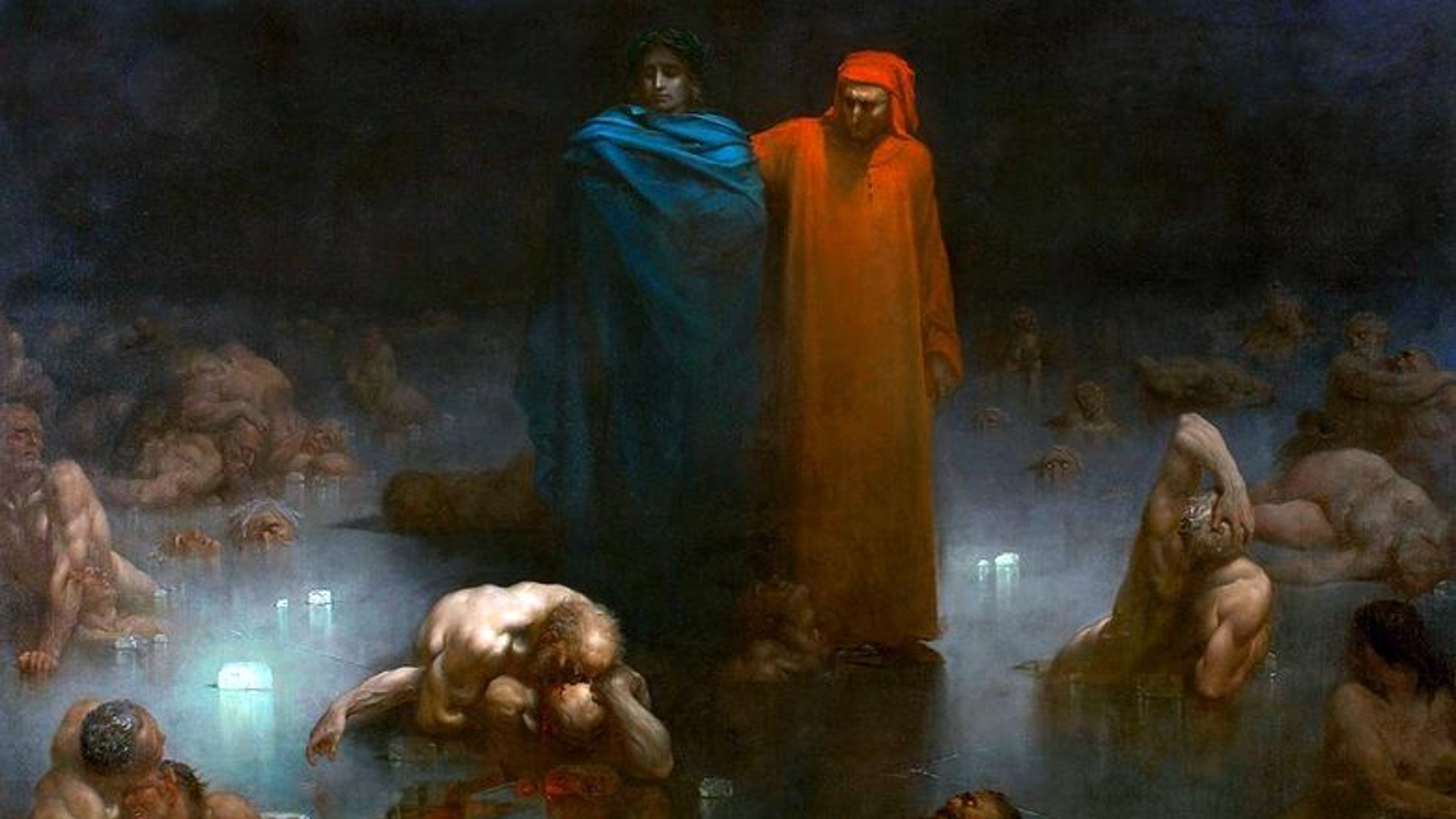

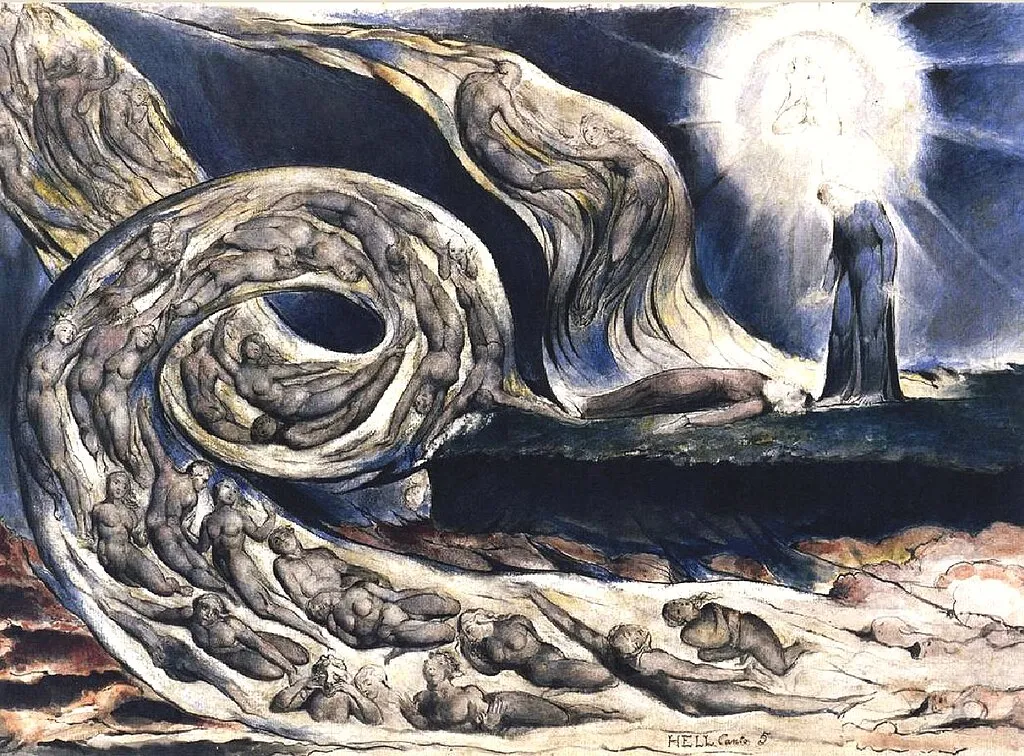

Dante Alighieri’s Inferno is a pillar of the Western literary canon. A whirlwind tour of the nine circles of hell, the allegorical poem has had volumes of scholarship dedicated to unpacking its secrets. Its vivid, and often grotesque, imagery has inspired artists such as Sandro Botticelli, Auguste Rodin, and William Blake. It was even made into a video game.

Alighieri’s other two poems of The Divine Comedy, Purgatorio and Paradiso, explore the realms of purgatory and heaven, respectively. But they don’t receive the love, attention, and adoration of the hell-bound original. That’s because heaven is — let’s face it — a little one note. Hell is where the drama happens.

Given its prominence in imagery and storytelling, it is surprising that hell doesn’t appear much in the Bible. In fact, most of its references to Satan’s scorching domain are the result of later translators mapping their views onto older, and quite distinct, concepts of the afterlife. This means hell as we understand it today is an afterlife the biblical writers had no real conception of.

Where in the hell?

Sheol is mentioned 66 times in the Hebrew Bible, and many versions of the Old Testament translate the word as hell. For example, the King James Bible renders Psalms 16:10 as “For thou wilt not leave my soul in hell; neither wilt thou suffer thine Holy One to see corruption.”

The exact meaning and etymology of the word Sheol is debatable. Some biblical scholars argue it is a synonym for the grave itself. Under this view, a more accurate translation of Psalms 16:10 might be: “For you will not leave my soul among the dead or allow your Holy One to rot in the grave.” Other scholars disagree and argue Sheol is a realm of the dead (see Job 10:21). Even then, Sheol is a far cry from hell. Rather than a realm designed to punish sinners, Sheol is a place where all souls congregate and exist in listless nothingness. There is no pain or suffering, but neither is there joy or celebration.

If not the Hebrew Bible, then surely hell is discussed at length in the New Testament? But even in the New Testament, references to hell are sparse. Jesus, Christianity’s central figure, and Saint Paul, its founding missionary, did preach about existential comeuppance. But in our earliest Christian writings — Paul’s epistles and the Gospels of Mark and Matthew — neither warned of a hellfire awaiting sinners.

Biblical scholar Bart Ehrman argues that a close reading of Jesus’ words shows this. In Mark and Matthew, Jesus preaches about the impending “Kingdom of God,” and by that, he didn’t mean a kingdom in heaven. Jesus envisioned a kingdom here on earth and that those who followed God’s laws would be bodily resurrected to live in this glorious new era. He believed it was coming soon, too — within a generation (Matthew 24:34).

The fate befalling those who turned their backs on God wouldn’t be an eternal sentence. They would simply be annihilated. Many of Jesus’ parables warn of this. The bad fish are discarded (Matthew 13:48). The trees that bear bad fruit are thrown into the fire (Matthew 7:16-20). The same happens to those dastardly goats separated from the holy sheep (Matthew 25).

While many of these parables evoke the image of fire, Ehrman points out that these fires destroy the unfaithful. Even if the fires burn eternally, those cast within aren’t said to. Their punishment is death in the face of eternal life.

“This appears to have been the teaching of both Paul and Jesus. But it was eventually changed by later Christians, who came to affirm not only eternal joy for the saints but eternal torment for the sinners, creating the irony that throughout the ages most Christians have believed in a hell that did not exist for either of the founders of Christianity,” Ehrman writes in Heaven and Hell.

Highway to hell

If not the Bible, then where did hell come from? The simple answer to that complex question — this is a “brief history” after all — is that hell is a collaborative effort of cultural exchange in the ancient Mediterranean region.

Jewish culture didn’t materialize in a vacuum. The neighboring — and, on more than one occasion, conquering — empires influenced it. Sometimes Jewish thinkers would adopt and adapt ideas from these cultures. Other times, they would reject them. But both changed Jewish theology over centuries.

For instance, Jewish apocalypticism viewed the world as a cosmic battleground between good and evil. As the view went, God’s enemies held dominion over the current era, but soon, God would conquer his enemies and usher in a utopian era. And apocalyptic thinkers were greatly influenced by Hellenistic culture after the conquests of Alexander the Great. This is evident in how they combined their biblical traditions with Greek motifs such as heavenly journeys and judgment of the dead.

“These Hellenistic parallels do not argue that the apocalyptic genre is derived from Hellenistic culture or that the Jewish apocalypses lack their own originality and integrity,” John Collins, an Old Testament scholar, writes. However, “the Hellenistic world furnishes some of the codes that are used in the apocalypses.”

Jesus’ worldview was steeped in apocalypticism, and in a strange twist, Saint Paul brought Jesus’ brand back to the Hellenistic world through his ministry. There, it mixed and mingled further with Greco-Roman concepts of the afterlife.

As the generations passed and Jesus’ promised Kingdom of God never materialized, these newly minted Christians got to thinking: What if they had misunderstood Jesus? What if the triumph of good over evil didn’t happen on Earth? What if the eternal life promised was in the spiritual sense, something along the lines of other idyllic afterlives? And if there are to be eternal rewards, then it isn’t much of a leap to think that the punishments must be eternal, too.

A place of agony

This evolution of Jesus’ message is seen in the later written books of the New Testament. Second Peter tells of how God cast the sinful angels into Tartarus (again, often mistranslated as hell). In the Rich Man and Lazarus — a parable that appears only in the Gospel of Luke — the rich man is said to suffer in Hades after death, while the saintly Lazarus enjoys an afterlife in Abraham’s bosom. (Heaven, it seems, was a work-in-progress at this time, too.)

Once conceived of, hell quickly took on an afterlife of its own. One of the earliest tours of hell is the Apocalypse of Peter. Written in the 2nd century, it tells of Saint Peter’s travels through the afterlife. The description of heaven is short and not very eventful; rather, it is in Peter’s hellscape that we recognize our modern conceptions taking shape.

Here, sinners are tormented according to their earthly misdeeds. Blasphemers are hung by their tongues. Murderers are bitten ceaselessly by venomous snakes and flesh-eating worms. Rich misers wear rags and are pierced by a pillar of fire. It’s display after display in a cruel shop of horrors, one that would make most modern readers queasy.

“The author of Peter had a voyeuristic, sadistic, and scatological bent that set the tone for later visions,” Alice Turner writes in The History of Hell. “Though we may recoil from Peter and regret its wide influence, it may be useful to know that at the time it was written the threat of torture was a new anxiety for Christian citizens [of Rome].”

Not one hell of a place, but many

That may seem like the end of the journey into hell, but like the fires fueling this inferno, hell just won’t stand still. Since the early Christians, each era of Western culture has refashioned hell in some way. Oftentimes, the changes are more a statement about their world than the next:

- The Middle Ages witnessed a smorgasbord of hells in popular stories and theater. Hell may be horrible, but at the time, it was certainly livelier than most people’s daily existence.

- Dante’s hell was, among other things, a proclamation against the Catholic Church’s wealth and involvement in politics.

- During the Baroque period, Jesuits retired hell’s more fiery tortures and reimagined them in terms of crowded urban squalor.

- By the Enlightenment, the very idea of hell was questioned. Voltaire proclaimed it ridiculous that a man should burn forever for stealing a goat (while also noting the connection between hell and Persian, Greek, and Egyptian afterlives).

All of which is to say: Hell is not a singular concept handed down to us from the Bible. It has many permutations, with each one serving as a spiritual placeholder for the best and worst of us.

On the one hand, it shows our desire for justice. If life will not play fair, then we can at least imagine an afterlife where the wicked and treacherous pay for their crimes, while their victims receive relief from earthly torments. On the other hand, hell houses our hate, intolerance, and savagery. It puts on full display our hidden desire to be proven superior over others — and to punish those who don’t conform to our beliefs.