5 classic books where the main character isn’t human

- Non-human protagonists allow readers to view the world from a fresh perspective.

- Throughout history, talking animals have provided an excellent source for allegory and satire.

- Some non-human protagonists resemble people, while others are completely and deliberately alien.

Being human, the vast majority of authors choose to write books about human beings. However, narratives need not unfold from the perspective of a person in order to convey interesting ideas and leave an impact on the reader. The more unusual an author’s viewpoint, the more creative possibilities present themselves during the writing process.

A good example of this is The Secret Life of Objects by Dawn Raffel. As its title suggests, this 2012 collection of short stories is written from the perspective of various inanimate things, including a button, a cake pan, and a shoelace that together bear witness to the lives of the humans that own and use them. Memoirs of an Imaginary Friend by Matthew Dicks is, as you might have guessed, written from the perspective of an imaginary friend — specifically, one that lives inside the mind of a young autistic boy. The Book Thief by Markus Zusak is narrated by a personification of death, traveling through Nazi Germany. There are even some books “written” by God, one of which — The Last Testament: A Memoir by David Javerbaum — is framed as an autobiography.

When written well, an unusual viewpoint allows the author to explore a theme or communicate a message. Surpassing more conventionally written narratives, books revolving around non-human characters allow readers to see the world in a new light. At times, they may even teach us valuable lessons about what being human really means.

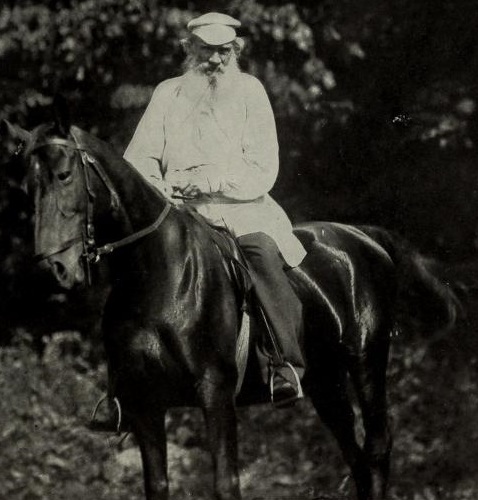

Leo Tolstoy’s “Kholstomer”

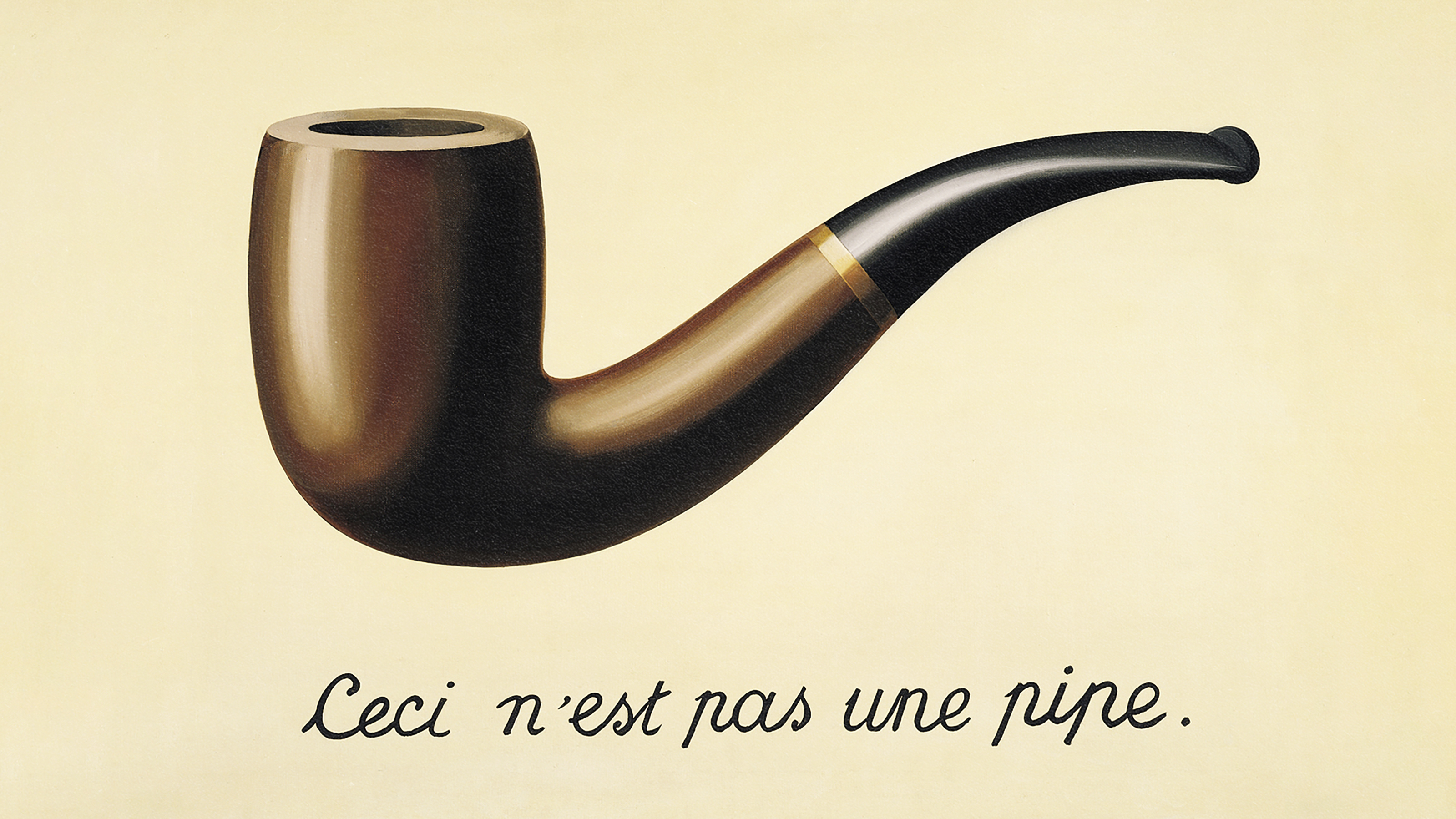

In his 1917 essay “Art as Device,” the Russian literary critic Viktor Shklovsky explains how he analyzes a work of literature. Where so many others turn to history, psychology, or an author’s personal biography to make sense of what they read, Shklovsky believed that texts should be allowed to speak for themselves and be observed in isolation from the world that exists outside their pages.

This means focusing only on what’s inside a book: its structure, metaphor, diction, and syntax. It also means looking for something Shklovsky termed “defamiliarization” or “estrangement.” Defined as an effect that every author should strive to produce, to defamiliarize is to make the familiar appear unfamiliar again — that is, to describe something, like an action or emotion, in such a way that the reader feels as though they are encountering it for the first time.

To further illustrate his point, Shklovsky turns to a little known story by Leo Tolstoy called “Kholstomer.” Far removed from celebrated works like War and Peace and Anna Karenina, it follows the life of a work horse as it is moved from one Russian estate to another. The fact that Kholstomer is a horse is not a trivial detail, as its limited perspective and inability to reason allows the animal to identify prejudices and injustices in society that any human protagonist would overlook.

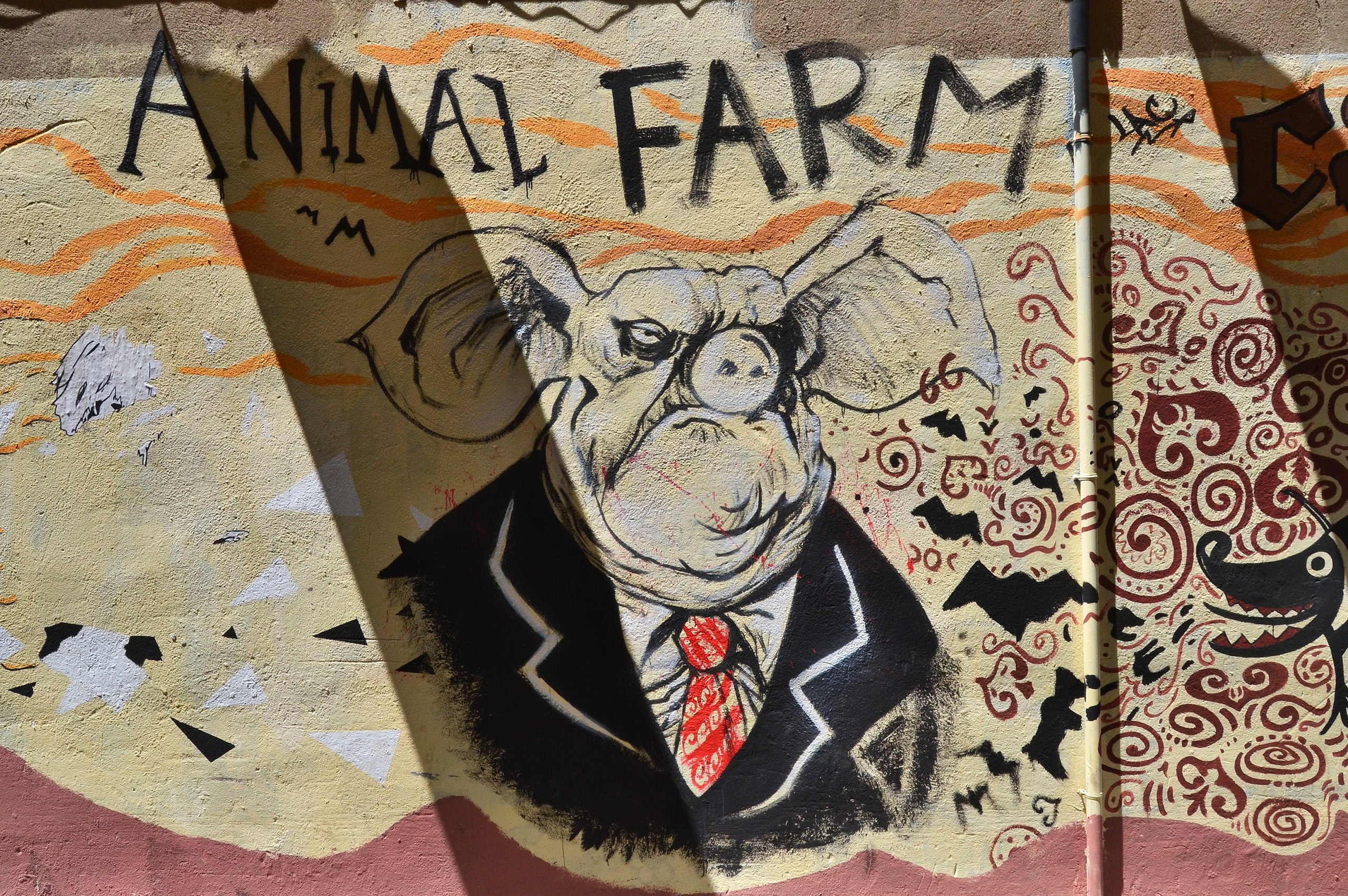

Reynaert the Fox versus Animal Farm

During the Middle Ages, authors used animal characters to satirize real-life individuals and institutions. In his 1250 story Of Reynaert the Fox, the Middle Dutch poet named “Willem die Madoc maecte” (“Willem who told tales”) replaces the nobility and clergy of his day with wolves, bears, and hares — all of whom are given their due by a clever fox that, through his pranks, punishes the evils of feudalism. Had Willem written Reynaert the Human, and mentioned his targets by their actual names, he might have lost his hands — or worse, his head.

Animal satire continued all the way into the 20th century. In his famous 1954 novella Animal Farm, essayist George Orwell substitutes the Soviet government for a farm and the Soviet people with farm animals. By doing so, the author somehow makes his critique more digestible and sophisticated at the same time. The czar is represented by a human farmer named Mr. Jones who, after years of abuse and neglect, is chased away by his own animals. The white pig leading the charge, Snowball, stands in for the intellectualism and idealism that drove the 1917 Russian Revolution, while the black pig Napoleon, who takes over the farm after hunting down Snowball, is a personification of Joseph Stalin.

But Orwell’s critique goes deeper still. The fact that Snowball and Napoleon are both pigs suggests to the reader that the things they embody — the two Russian Revolutions of 1917 and their resulting forms of government — are, to some extent, connected. Also portrayed as a pig is the philosopher Karl Marx who, in the form of an aging porker called Old Major, encourages his fellow animals to stand up against Mr. Jones. Last but not least, the guard dogs Napoleon uses to seize power symbolize the Soviet secret police as well as, arguably, the Communist Party’s most devoted followers. Just as Napoleon raised the dogs since they were pups, so did an entire generation of Russians grow up under Bolshevik rule.

All Tomorrows and West of Eden

While some non-human protagonists are supposed to remind readers of their own humanity, and how it can show up in places they least expect it, other authors delight in creating narratives that, through their unusual perspectives, feel genuinely alien. Such is often the case for narratives written from the viewpoint of extraterrestrials, like C.M. Kösemen’s science fiction classic All Tomorrows, in which an omnipotent alien race, the Qu, uses genetic engineering to devolve humanity into dozens of otherworldly lifeforms.

Some of the most “alien” characters in fiction aren’t aliens at all, but dinosaurs. In West of Eden (not to be confused with John Steinbeck’s East of Eden), the author Harry Harrison envisions an alternative universe in which the asteroid that caused the Cretaceous-Tertiary mass extinction event misses the Earth, allowing dinosaurs to survive and eventually develop sentience. The civilization created by this new species, called the Yilanè, is nothing like our own, and Harrison goes into lengthy detail explaining how the differences in social organization relate to their unique biology and evolutionary history.

The Yilanè evolved from a small marine reptile related to the fearsome mosasaurs. Over the course of their evolution, they returned to living on land, learned to walk upright, and grew opposable thumbs to enable them to manipulate their environment more easily. The basic organization of Yilanè life begins with their language, which consists not just of sounds but also of gestures made with their limbs and tails, as well as with their skin, which like a chameleon’s changes color to reflect their mood. Because this process is unconscious and uncontrollable, the Yilanè lack the ability to lie to one another. Because male Yilanè die after reproducing, society is matriarchal, with the males being raised in segregated communities until they are old enough to breed. Rigid social norms keep their society homogenous — a homogeneity further enforced by biology, as a vestigial hormonal mechanism in their hypothalamus once used for hibernation will cause any Yilanè that becomes physically separated from their community to die.