How the “Dune” screenwriters adapted an “unadaptable” book

- Frank Herbert’s Dune has proven to be a difficult story to adapt for cinema.

- While working on the film, screenwriter Eric Roth tried to humanize its superhuman characters.

- At the same time, Dune: Part One and Dune: Part Two preserve the otherworldly atmosphere that made the original novel such a success.

Denis Villeneuve wasn’t the first person to adapt Frank Herbert’s 1965 science fiction novel Dune for the big screen, but he is the first to have done so successfully.

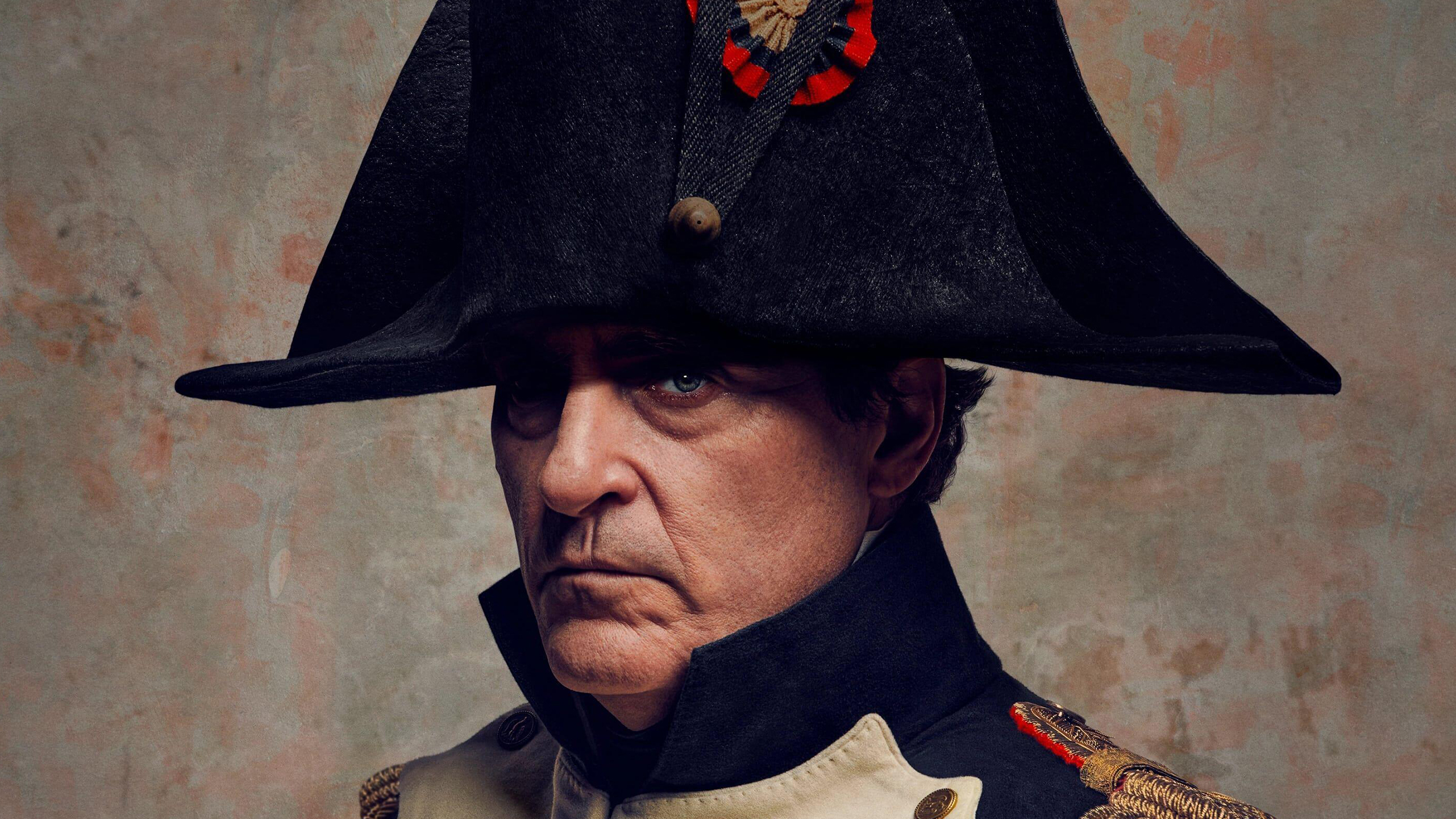

In the 1970s, the Chilean-French filmmaker Alejandro Jodorowsky came close. He handed art design to renowned comic book artist Mobius, who produced hundreds of pieces of concept art, bringing the desert planet of Arrakis to life. He managed to cast the legendary Orson Welles in the role of the antagonist, the obese Baron Vladimir Harkonnen, by promising to hire the retired actor’s favorite Parisian chef as his personal cook. Musician Mick Jagger was brought on to play secondary antagonist Feyd-Rautha, the Baron’s psychotic nephew, while Shaddam IV, the Emperor of the Known Universe, would have been played by none other than surrealist painter Salvador Dalí. Jodorowsky’s vision seemed too good to be true. It was. Unwilling to compromise on the film’s whopping 14-hour runtime, Jodorowsky’s Dune languished in development hell, where it remains to this day.

Another iconic filmmaker, David Lynch, the director of Mulholland Drive, Blue Velvet, and Twin Peaks, tried his hand at adapting Dune the following decade. Although his interpretation did make it to theaters in 1984, it’s since gone down as one of the worst films ever made. If a great movie existed somewhere in the editing room, audiences never got the chance to see it. Similarly unwilling to compromise on a shorter runtime, Lynch lost control of the film’s final cut to his producers. He later referred to production as a “75% percent nightmare,” and not in a good, Lynchian way.

The fate of these promising projects left many Dune fans fearing that their favorite franchise — with its sprawling narrative, complex themes, and otherworldly set pieces — was “unfilmable.” This fear persisted until the release of Villeneuve’s Dune: Part One in 2021. Receiving positive reviews and earning $434.8 million at the box office against a budget of $165 million, its critical and commercial success took even the most cautiously optimistic audience members by surprise. Dune: Part Two, which premiered on March 1, 2024, performed even better than the prequel, and is likely to go down as one of the best films of the year.

This begs the question: How did Villeneuve succeed where other, equally talented filmmakers did not? While state-of-the-art visual effects undoubtedly play a central part in the equation — as does the star power of Timothée Chalamet, Zendaya, and Jason Mamoa, who play protagonist Paul Atreides, love interest Chani, and mentor Duncan Idaho, respectively — the film’s secret ingredient arguably lies with how screenwriters Eric Roth and John Spaihts tackled their source material, which is as expansive and treacherous as the deserts of Arrakis itself.

In an interview with Big Think, Roth explains how he and his team finally figured out how to adapt the allegedly unadaptable novel.

Challenge 1: Setting the stage

“I was never a fanboy of the books, to be honest,” Roth, a veteran screenwriter known for penning the scripts of Oscar-winning movies like Forrest Gump and, more recently, Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon, confessed. Like almost every American youth coming of age in the psychedelic 60s, he read Herbert’s Dune almost immediately after its publication. Still, Herbert didn’t speak to Roth to the same extent as other science fiction authors like Ray Bradbury and Arthur C. Clarke did. He felt the novel had a strange, off-putting quality: “One thing that always bothered me was this Duncan Idaho. Great character, but where the hell does that name come from?” The narrative, which in subsequent books spans several thousands of years, became too cerebral to hold his interest.

Roth explains that Villeneuve didn’t approach him because he loved the novel, but because the two had had a fruitful relationship working on the 2016 sci-fi film Arrival, adapted from a 1998 short story by Ted Chiang. In hindsight, Roth’s lukewarm attitude toward the source material turned out to be a good thing. Where an emotionally attached writer might try to translate the novel word for word, Roth was able to look critically at what parts of the story did and didn’t need to make it into the script.

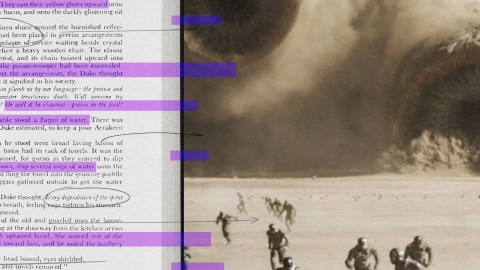

“The book is over 600 pages,” Roth explains. “With screenplays, a page equals about a minute, which is a pretty hard and fast rule. If you only have 120, maybe 130 pages to work with, you’ve got to make certain decisions about what you’re dramatizing. It’s a Herculean job considering all the rituals and gadgets mister Herbert invented.”

Even when splitting the novel into two films — something neither Jodorowsky nor Lynch wanted to do — Roth and Spaihts had to omit a significant amount of material. Notably absent from the first film is the dinner scene that precedes the Harkonnen attack on Arrakis, which the Emperor handed over to House Atreides as part of his plot to destroy their bloodline, and which sees Paul’s family attempting to figure out who among them is conspiring with the Harkonnens. Characters alive and active in the book, including the Atreides mentat Thufir Hawat, and Harkonnen henchman Piter de Vries, do not appear in the second installment. The list goes on.

The decision to split the book into two films was made early in the writing process, with Roth putting together a 180-page treatment to convince Herbert’s son Brian to hand over the film rights. The result is somewhat reminiscent of Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy, with the first film focusing mostly on exposition — introducing the history, geology, and sociology of the Dune universe — and the second on the plot. In other words, Dune: Part One ran so that Dune: Part Two could fly, or, rather, surf on the scaly back of a sandworm.

Challenge 2: Discovering Dune’s humanity

Ultimately, Roth, Spaihts, and Villeneuve faced the same obstacle every other film adaptation of an epic fantasy novel faces: Crafting a narrative that doesn’t let the source material’s encyclopedic lore and extraterrestrial setting distract from the personal story at its center.

This was especially tricky with Dune, which — while it resembles other successful franchises like George R.R. Martin’s Game of Thrones on a surface level — isn’t about the struggles of individual characters so much as it’s about the abstract ideas they represent. While Paul Atreides and Lady Jessica are just as complex and layered as Tyrion Lannister and Daenerys Targaryen, they just aren’t nearly as relatable. Übermenschen shaped through centuries of spiritual and technological evolution, they have learned to keep their emotions under control and rarely make decisions that aren’t based on cold, calculated, quasi-computational reasoning. This makes them ideal protagonists for a novel, which can explore their unusual thought processes in detail, but not necessarily for a film, which is all about action.

Writing the screenplay, Roth tried to humanize his superhuman characters as much as possible. For Paul, he did this by identifying the character’s inner conflict, which on closer inspection has a lot in common with other characters losing and avenging their wrongfully murdered fathers, like Hamlet or Simba from Disney’s The Lion King. “Timothée’s character arc,” Roth says, “is that of a boy who needs to become a man, while also being burdened by this notion that he’s going to become a prophet.” In Dune: Part Two, Spaihts adds intrigue to the desert-dwelling Fremen by making the southern tribes more superstitious than the northern ones, leading them to bicker about whether or not Paul is their prophesized savior.

To obtain the rights from Brian Herbert, Roth and his team had to prove that they, despite making small changes here and there, “wouldn’t wander too far from the book.” While they certainly humanized the characters, they also managed to maintain the (for lack of a better word) weirdness of Dune. Indeed, part of what made the original novel so successful is that it really feels like this story is taking place in the far-off future, on worlds radically different from Earth, populated by cultures that have diverged so far from ours that they have become all but alien, with psychic nuns and giant sandworms and a dude who, for some wonderfully inexplicable reason, is named Idaho.

Through thoughtful art design, sound design, and cinematography, Villeneuve was able to translate this elusive atmosphere to the big screen. This, combined with having a slightly more relatable narrative, allowed Dune: Part One and Dune: Part Two to achieve a comfortable balance between familiar and unfamiliar that previous adaptions — made and unmade — did not possess. And that, in a nutshell, is why it worked.