We must learn from science that “intelligent failure” is the key to success

- In science, a thoughtful hypothesis that is not supported by data is the “right” kind of wrong. Scientists value “intelligent failure.”

- High-performing individuals aren’t used to making mistakes, but learning to laugh at ourselves prepares us for failure.

- Mistakes can happen when knowledge already exists but isn’t used. However, intelligent failures always inform new work.

Although most of us are familiar with the concept of DNA — the nucleic acids that determine so much of who we are — few of us have tried to manipulate these tiny naturally occurring chemicals to enhance their application in lifesaving therapeutics or game-changing nanotechnologies. That is what Dr. Jennifer Heemstra, working with the other members of her thriving research laboratory at Emory University, does for a living.

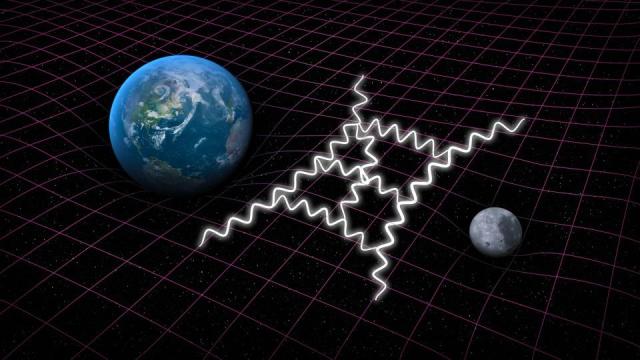

On the frontier in any scientific field, a thoughtful hypothesis not supported by data is the right kind of wrong. Scientists don’t last long in their fields if they can’t stand to fail. They intuit the value intelligent failure brings. It would be a lie to claim these failures aren’t disappointing. They are. Like Olympic bronze medalists, however, scientists and inventors learn healthy ways to think about failure.

And Dr. Heemstra is a scientist who not only practices this healthy thinking, she also preaches it — to the students in her lab and in tweets, articles, and videos.

I met with Jen on Zoom on a summer day in 2021. Scientists are among the most resilient and thoughtful practitioners of intelligent failure, and I wanted to learn more from Jen about how an intelligent failure might play out.

Behind her, on the shelves behind her desk, are various models and action figures she’s collected. She points to one and says it’s named Steve, after a PhD student, Steve Knutson, who used a chemical reagent called glyoxal (an organic compound often used to link other chemicals in scientific experiments) to react with nucleotides in single-stranded RNA. When I ask why this might be important (revealing my relative ignorance about chemistry), Jen says, “Aha!” and explains that the lab had been ecstatic because of how many avenues of research and development glyoxal opened up. In addition to applications for controlled or time-release therapeutic drugs, they’d invented a kind of scientific tool for other chemists working in synthetic biology or research to control different gene circuits.

What about failure? Apparently, even someone as comfortable with failure as Jennifer Heemstra naturally begins a failure story with the ending — the successful outcome. Which only reinforces how difficult it is to talk about failure.

Jen takes a step back. Speaking rapidly, she explains that in trying to develop a method for isolating certain RNAs, they realized that it wouldn’t happen when the RNA was folded, or double stranded. So the first problem was to unravel the RNA, a necessary step in getting a protein to bind. Steve began to experiment. Would adding a new reagent (an ingredient used to cause a chemical reaction) already in the lab work?

It didn’t work.

Salt helps RNA fold. What if he experimented with depriving the RNA of salt? This didn’t work either. Steve was disappointed. But not devastated, as he might have been had Jen not worked so hard to create an environment in the lab where the focus is on learning and discovery. As she explains, “High-performing individuals aren’t used to making mistakes. It’s important to learn to laugh at ourselves or we’ll err on the side of being too afraid to try.”

Success in new territory depends on a willingness to endure the right kind of wrong.

Her passion for the central role embracing failure plays in science research has led Heemstra to write about how students, and especially women, can easily be discouraged from pursuing careers in science, stating in a tweet, “The only people who never make mistakes and never experience failure are those who never try.” But really, Steve’s failures were not mistakes.

Mistakes are deviations from known practices. Mistakes happen when knowledge about how to achieve a certain result already exists but isn’t used. Such as the time when Jen was a graduate student and collected weird data simply because she was using the pipette incorrectly. Proper pipette usage promptly produced data that made sense. She laughs at this story, too, explaining that she tries to create a lab culture where people can “laugh at and normalize silly mistakes.”

That the protein failed to bind on double-stranded DNA when it had succeeded in binding on single-stranded RNA was not, however, a “silly mistake.” It was the undesired result of a hypothesis-driven experiment. A failure, yes, but an intelligent failure — and an inevitable part of the fascinating work of science. Most important, that failure would inform the next experiment.

Clearly, there was more to learn about how to unfold RNA. Steve went back to the literature and found a paper written by Japanese biochemists in the 1960s, published in a German scientific journal, detailing the use of glyoxal in other, not unrelated, applications. He started to wonder about using glyoxal and set up an experiment with it.

Eureka! With some tweaking, the glyoxal allowed him to cage and re-cage the nucleic acids and restore total function. While not an announcement to flash electronically in 20-foot letters on a Times Square billboard, for Jen and Steve as research scientists it was cause for celebration, and better yet, it led to new research questions. Their story shows how success in new territory depends on a willingness to endure the right kind of wrong — the intelligent kind.