Why the free will debate hinges on intent

- Intent features heavily in issues about moral responsibility — and a huge percentage of research into free will centers on intent.

- While it may seem that we are free to do as we intend, we are never free to "intend what we intend," according to author and neurologist Robert M Sapolsky.

- Maintaining belief in free will by failing to ask where intent comes from in the first place is myopic.

Two men stand by a hangar in a small airfield at night. One is in a police officer’s uniform, the other dressed as a civilian. They talk tensely while, in the background, a small plane is taxiing to the runway. Suddenly, a vehicle pulls up and a man in a military uniform gets out. He and the police officer talk tensely; the military man begins to make a phone call; the civilian shoots him, killing him. A vehicle full of police pulls up abruptly, the police emerging rapidly. The police officer speaks to them as they retrieve the body. They depart as abruptly, with the body but not the shooter. The police officer and the civilian watch the plane take off and then walk off together.

What’s going on? A criminal act obviously occurred—from the care with which the civilian aimed, he clearly intended to shoot the man. A terrible act, compounded further by the man’s remorseless air—this was cold-blooded murder, depraved indifference. It is puzzling, though, that the police officer made no attempt to apprehend him. Possibilities come to mind, none good. Perhaps the officer has been blackmailed by the civilian to look the other way. Maybe all the police who appeared on the scene are corrupt, in the pocket of some drug cartel. Or perhaps the police officer is actually an impostor. One can’t be certain, but it’s clear that this was a scene of intent-filled corruption and lawless violence, the police officer and the civilian exemplars of humans at their worst. That’s for sure.

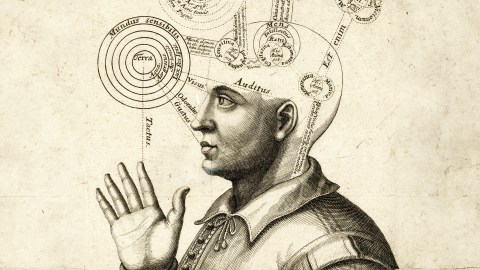

Intent features heavily in issues about moral responsibility: Did the person intend to act as she did? When exactly was the intent formed? Did she know that she could have done otherwise? Did she feel a sense of ownership of her intent? These are pivotal issues to philosophers, legal scholars, psychologists, and neurobiologists. In fact, a huge percentage of the research done concerning the free-will debate revolves around intent, often microscopically examining the role of intent in the seconds before a behavior happens. Entire conferences, edited volumes, careers, have been spent on those few seconds.

Nevertheless, all this is ultimately irrelevant to deciding that there’s no free will. This is because this approach misses 99 percent of the story by not asking the key question: And where did that intent come from in the first place? This is so important because, as we will see, while it sure may seem at times that we are free to do as we intend, we are never free to intend what we intend. Maintaining belief in free will by failing to ask that question can be heartless and immoral and is as myopic as believing that all you need to know to assess a movie is to watch its final three minutes. Without that larger perspective, understanding the features and consequences of intent doesn’t amount to a hill of beans.

Let’s start off with William Henry Harrison, ninth president of the United States, remembered only for idiotically insisting on giving a record-long two-hour inauguration speech in the freezing cold in January 1841, without coat or hat; he caught pneumonia and died a month later, the first president to die in office and the shortest presidential term.

With that in place, think about William Henry Harrison. But first, we’re going to stick electrodes all over your scalp for an electroencephalogram (EEG), to observe the waves of neuronal excitation generated by your cortex when you’re thinking of Bill.

Now don’t think of Harrison—think about anything else—as we continue recording your EEG. Good, well done. Now don’t think about Harrison, but plan to think about him whenever you want a little while later, and push this button the instant you do. Oh, also, keep an eye on the second hand on this clock and note when you chose to think about Harrison. We’re also going to wire up your hand with recording electrodes to detect precisely when you start the pushing; meanwhile, the EEG will detect when neurons that command those muscles to push the button start to activate. And this is what we find out: those neurons had already activated before you thought you were first freely choosing to start pushing the button.

But the experimental design of this study isn’t perfect, because of its nonspecificity—we may have just learned what’s happening in your brain when it is generically doing something, as opposed to doing this particular something. Let’s switch instead to your choosing between doing A and doing B. William Henry Harrison sits down to some typhoid-riddled burgers and fries, and he asks for ketchup. If you decide he would have pronounced it “ketch-up,” immediately push this button with your left hand; if it was “cats-up,” push this other button with your right. Don’t think about his pronunciation of ketchup right now; just look at the clock and tell us the instant you chose which button to push. And you get the same answer—the neurons responsible for whichever hand pushes the button activate before you consciously formed your choice.

Let’s do something fancier now than looking at brain waves, since EEG reflects the activity of hundreds of millions of neurons at a time, making it hard to know what’s happening in particular brain regions. Thanks to a grant from the WHH Foundation, we’ve bought a neuroimaging system and will do functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) of your brain while you do the task—this will tell us about activity in each individual brain region at the same time. The results show clearly, once again, that particular regions have “decided” which button to push before you believe you consciously and freely chose. Up to ten seconds before, in fact.

Did the person intend to act as she did? When exactly was the intent formed? These are pivotal issues to philosophers, legal scholars, psychologists, and neurobiologists.

Eh, forget about fMRI and the images it produces, where a single pixel’s signal reflects the activity of about half a million neurons. Instead, we’re going to drill holes in your head and then stick electrodes into your brain to monitor the activity of individual neurons; using this approach, once again, we can tell if you’ll go for “ketch-up” or “cats-up” from the activity of neurons before you believe you decided.

These are the basic approaches and findings in a monumental series of studies that have produced a monumental shitstorm as to whether they demonstrate that free will is a myth. These are the core findings in virtually every debate about what neuroscience can tell us on the subject. And I think that at the end of the day, these studies are irrelevant.