A revolting thought experiment tests the limits of philosophical exploration

- In a recent philosophy paper, the pseudonymous Fira Bensto argues that if zoophilia provides pleasure for animals and people, there is no reason to forbid it.

- Bensto further argues that animals can express consent or dissent toward sexual interactions through behavioral cues.

- While Bensto's arguments may be philosophically sound, moral norms and prejudices play a significant role in shaping our society's laws and taboos.

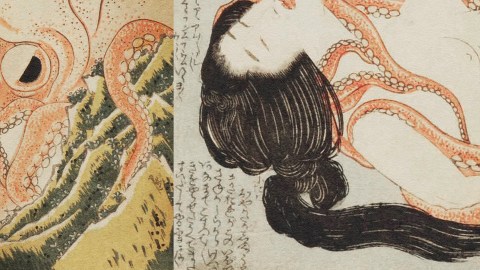

You may want to put down your coffee and finish your cornflakes; this thought experiment isn’t for everyone. It comes from a paper recently published in the Journal of Controversial Ideas and written by the pseudonymous philosopher Fira Bensto. It’s a story about Alice and her dog.

“Alice self-describes as being in a romantic relationship with her dog. She cares a lot about his well-being and strives to ensure that his needs are fulfilled. They often sleep together; he likes to be caressed, and she finds it pleasant to gently rub herself on him. Sometimes, when her dog is sexually aroused and tries to hump her leg, she undresses and lets him [copulate]. This is gratifying for both of them.”

When your eyebrows finally lower and your gawping mouth closes again, there’s a question to consider: What is wrong with Alice’s story? Yes, canophilia might not be your thing, but if it’s Alice’s, what philosophical reason have we to deny her and her dog such pleasure?

This debate has come to light recently because Peter Singer, the famous philosopher at Princeton University, has come out encouraging people to read Bensto’s paper. It must be said that Singer has not endorsed the article. While a founding co-editor of the journal, he has explicitly said that the promotion or publication of a piece does not mean he necessarily agrees with it. (Although his public response was oddly ambiguous.)

Here, we will dive into two related questions: Is having sex with animals always wrong, and are there some things that go beyond a philosopher’s understanding of right and wrong?

Debating pleasure and consent

There are three elements to Bensto’s argument. They are:

- Zoophilia does not cause harm but invites pleasure.

- Zoophilia can involve a degree of meaningful consent.

- The principal reasons for disallowing zoophilia come from non-moral, anthropomorphic grounds.

To defend the first argument, Bensto argues that while some zoophilia does certainly harm animals, there equally might be “positive evidence that the animal is having a pleasant experience.” When a sexual act does “not seem to cause any pain, bodily damage, or psychological distress to an animal,” we would need other grounds for forbidding it.

The only other reasonable ground, Bensto attests, has to do with consent. Even if bodily pleasure is apparent, when we’re dealing with sexual ethics, we need to guarantee consent.

That leads to Bensto’s second argument. He argues that animals can express consent or dissent toward sexual interactions through behavioral cues, challenging the notion that they are incapable of such communication. If you held out some food for a deer to eat and it ate it, you can take this as a “choice” — or consent. The same is true for sexual behaviors.

“When it comes to sex, there is a wide range of species- and individual-dependent cues that indicate consent,” Bensto writes.

Does the moral world revolve around us?

Bensto’s arguments about animal consent are mostly underpinned by his claim that we ought not to wrongly project human understandings of “consent” onto animals. For example, philosophers of consent have cited many necessary requirements for consensual activity. Bensto picks out three: The agents need a degree of free will, they need to be fully informed about the decision, and there needs to be as close to an equal balance of power as possible. In all three cases, according to each of their criteria for consent, animals cannot be said to have consented.

For Bensto, though, these criteria wrongly anthropomorphize consent. Consent can and does exist in the animal world. Dogs choose to respond to your call. A deer consents to eat food from your hand. Yes, animals cannot consent to sex in the same way as humans, but there is consent. What’s more, our notions of “power dynamics” and “power inequalities” are things that exist only in a human social world. Unless more is done to flesh out what is meant by power inequalities from an animal’s perspective, then the notion remains limited to the human level. All of this is to say that we should consider the sexual consent of an animal’s understanding of sex.

Down the philosophical rabbit hole

Bensto’s paper is cleverly argued. It’s philosophically sound and makes some great points. But in its pages lies a curious psychological phenomenon: When you spend a lot of time in the esoteric nooks of an academic paper or topic, you start to think differently. It’s as if your eyes have gotten used to the dark, and when someone turns on the lights, it’s blinding and painful. The same is true for a lot of “controversial” ideas. They are initially convincing and hard to rebut, yet they leave you with a bitter aftertaste of sophistry.

Our moral compass is not exclusively, nor even predominantly, defined by rational philosophizing. The laws that govern society are even less so. As the journalist Auron MacIntyre argues, this is not always a bad thing because rationality “is not the only way in which we interact with society.” MacIntyre discusses the issue in terms of “moral prejudices,” which establish taboos for certain things. It might be hard to philosophically disallow necrophilia, cannibalism, zoophilia, and sibling incest, but our collective prejudices have little trouble doing so. (What’s more, it could also be argued that these aren’t purely socially constructed, considering some of our prejudices and taboos likely stem from natural disgust responses, a psychological system that humans evolved to help avoid pathogens.)

A popular position is to say, “Well, let’s disregard prejudices; they’re the superstitious nonsense that fueled witch hunts and the Dark Ages.” MacIntyre’s point, though, is that these prejudices — formed through cultural, historical, and emotional contexts — act as bulwarks against moral chaos. Our moral norms are not argued in papers; they have been developed over millennia. Just because we cannot immediately see the point of something does not mean we should burn it down. Often “moral barriers are placed there for a reason and are placed well ahead of the actual danger.”

That bitter aftertaste of sophistry is not a primitive hangover to be ignored. It’s a tool that’s served us well. Yes, it is not always right. Prejudices and traditions can be things of oppression and bigotry. But we should still pay them good heed.