A brief history of (linear) time

- The history of philosophy does not give us a uniform understanding of time. In fact, it was one of the most heated debates in Ancient Greece.

- The reason why we see time as "linear" is because of Christianity. The idea of Genesis (at the start) and Judgement Day (at the end) gives us a narrative — a linear view of time.

- The world of our experience does not obviously lean one way or the other concerning time. Perhaps, as Aristotle did, we should just see time as an expression of change.

It’s a fundamental part of human nature to invent different ways of seeing the world. Our cultural, historical, and personal upbringing all play their part, providing concepts and belief structures that act as a lens through which we interpret reality. A small boy, hundreds of years ago, would look out into a dark forest and hear monsters prowling within. A medieval mother would open the windows and buy fragrant flowers because she thought that bad air was what sickened her child.

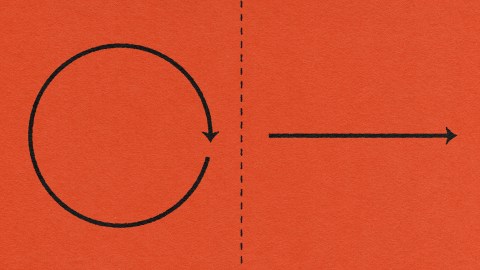

Today, those born into a Western intellectual tradition (at least those of us outside of physics departments) most often see time as linear. Just as we all divide and sort the world according to us, time is no different. A life has a beginning and an end. In so much of how we understand the world, time is bookended by two final points. Everything exists along a line with “before” at one end and “after” at the other. At the middle of that line lies us — reading this sentence.

But why is it that our conception of time — only one possible worldview — came to dominate so much of our understanding (especially in the Western intellectual tradition)?

A confusion in time

For once, it didn’t all begin with the Ancient Greeks. In fact, the Greek philosophers had some of their best, and most heated, debates about what time was. Antiphon believed time didn’t “exist” but rather was a concept to measure the world (something Kant would substantiate some 2,000 years later). Parmenides and Zeno (of the paradoxes) saw time as an illusion. Their argument was that since time meant everything must change, and since there were at least some things (like mental representations) that didn’t change, time cannot exist.

The only person who really saw time as a thing that had a “beginning” was Plato, who thought time was created by the Creator (what this Creator was doing before time is, quite frankly, a riddle). Plato’s view was only one, and not necessarily a popular one. Even his student, Aristotle, thought time wasn’t an independent thing but only a relational concept between objects.

But all that mattered was that the Christians loved Plato. The early Christian Church Fathers quickly realized that their account of creation and the Biblical account of the Last Judgement could map really well onto this linear view of time.

Heirs to Christian thought

So, we cannot find any definitive or universally accepted account of time — let alone linear time — in Ancient Greece. For that, we needed some kind of “beginning” and “end” to the line of time. We needed, in short, Genesis and Judgement Day.

A lot of the Bible is about suffering. It’s about the exile, persecution, and attempted genocide of the Jewish people. There are stories of martyrs and saints thrown to lions. What good, then, was a God if he couldn’t protect his people? And what justice is there to the idea that your oppressors get away with it unscathed? The answer came in the idea of Judgement Day — a final “end of days” apocalypse where sinners are punished, and the holy are rewarded.

Not only was Judgement Day a balm to all this suffering, but it also acted to structure the entire universe. Time was not some illusion, nor was it an infinite cycle. Rather, it was a deliberate narrative, written and overseen by God — our God. He had a plan, and “today” is only one step along the way He laid out for us. The Church Fathers and various councils that were charged with putting together the official, orthodox Bible knew very well they were laying out a story like every other: It begins, the characters grow and change in the middle, and it ends.

Sacred Time

The implications of this view — that God has created the universe with a narrative in mind — is that everything happens for a reason. It sets us up to believe there’s order in the madness and purpose in the chaos. This idea, called “Sacred Time,” gave meaning to Christians and is something that still infuses how we see the world. There are many reasons to be optimistic about the future, but the default position that “modern means better” is one that owes itself very much to a Christian view of time.

As theologian Martin Palmer puts it, “a huge amount of social philosophy, socialism, and Marxism throughout the 19th and 20th centuries belongs to the notion that history is inexorably moving towards a better world. This utopia/apocalypse tension is one that, to this day, shapes the social policy of socialist parties around the world.”

In short, when we say, “things will work out alright in the end,” there’s a lot hinging on that word: end.

Time is change

If you try to strip away all the ideological baggage with which we’re born, there’s not much that points toward linear time. The sun will rise and fall. Winter will pass and come back around with snowy regularity. History repeats itself. It’s why, across so much of human history, time is not viewed as a finite, closed line, but an infinite, repeating circle.

The Maya and Inca mythologies heavily featured cyclical and never-ending stories. In Indian philosophy, the “wheel of time” (Kalachakra) sees the ages of the universe come around over and over again. The Greek Stoics (and, later, Friedrich Nietzsche) offered a version of “eternal recurrence” — where this world, and this reality, would come around again, exactly the same way.

Of course, time is a hugely complex issue, and one which even today we’re having to unravel (I recommend reading this for a primer on the science of time). But, philosophically and phenomenologically, Aristotle hit the nail on the head. As Carlo Rovelli explains in his book, The Order of Time, “Time, as Aristotle suggested, is the measure of change; different variables can be chosen to measure that change, and none of these has all the characteristics of time as we experience it. But this does not alter the fact that the world is in a ceaseless process of change.”

The world changes. Be it an illusion or real, linear, or cyclical, change happens. Maybe time is just the language we use to try to explain that.