Hidden trauma: Do psychedelics reveal memories or create fake ones?

- Psychedelics have been reported to help individuals access and process deeply buried memories.

- However, psychedelic research raises concerns about the potential for psychedelics to enhance suggestibility and create false memories, mirroring debates from the "memory wars" era.

- Despite the compelling anecdotes, research highlights the complex nature of memory and the need for cautious interpretation of psychedelic-induced recollections.

Can psychedelics help people unearth and emotionally process significant memories, including traumatic memories that might be lurking below conscious awareness? Anecdotal evidence suggests they can. In the film Trip of Compassion, we hear from three survivors of separate traumas who said taking MDMA helped them revisit and heal from their experiences. And in courageous acts of vulnerability, two influential figures in the psychedelic space, Tim Ferriss and Katherine MacLean, have publicly shared their stories of recovering memories of sexual abuse under psychedelics — MacLean under psilocybin, as described in her book Midnight Water, and Ferriss under ayahuasca, mushrooms, and meditation, as noted in his podcast.

The media and research literature are full of countless anecdotes of psychedelics revealing hidden memories. But alongside what are undoubtedly some real and heart-rending personal accounts, there’s reason to be skeptical about the veracity of the memories retrieved while under the influence of psychedelics. After all, psychedelics have also been shown to increase suggestibility and enhance false memories — effects that understandably raise suspicions about retrieved memories, similar to suspicions in the “memory wars” of the 1990s, a series of debates on the scientific validity of repressed memories, uncovered trauma, and the perils of memory recovery therapy.

So how do we reconcile these two narratives, and is it really as black or white as siding with science or survivor?

Psychedelics and hidden memories

The root of the issue dates back more than six decades to the first wave of psychedelic research.

“One of the striking things about LSD treatment is the way in which the majority of the patients regress into childhood and appear to remember things which were apparently forgotten,” wrote psychedelic psychotherapist Ronald Sandison in 1959. “In a number of cases it has been possible to ascertain from other sources that the events described by the patient did, in fact, happen, and this has been confirmed by some of my colleagues.”

Stanislav Grof, Humphrey Osmond, and other clinicians practicing with psychedelics reported similar findings at the time. However, others reported (and have since reported) impaired or false memories under psychedelics, and concerns about false autobiographical memories in psychotherapy, let alone psychedelic psychotherapy, have been voiced since the time of Jung.

“This concern is highlighted further by the fact that it is not uncommon for patients to report remembering being born or even remembering previous lives,” wrote psychedelic researcher and philosopher Aidan Lyon in his 2023 book Psychedelic Experience: Revealing the Mind. “While one may wish to be open-minded about such reports, they certainly don’t fit well with cognitive science, and so one might reasonably choose to be suspicious about them. For all we know, psychedelic-induced recollections of real memories may be the exception rather than the norm.”

A 2000 study found that subjects who reported recovered memories of childhood sexual abuse were more susceptible to false memories, findings which were replicated in 2005. What’s more, the lingering notion that false memories may sometimes be “uncovered” during regular psychotherapy, paired with the tendency of psychedelics to increase suggestibility, invites a cautious treatment of the topic.

Despite reservations such as these, there is compelling anecdotal evidence that psychedelics can reveal hidden memories. But many questions remain — including questions about the nature of memory itself.

Encoding vs. retrieval

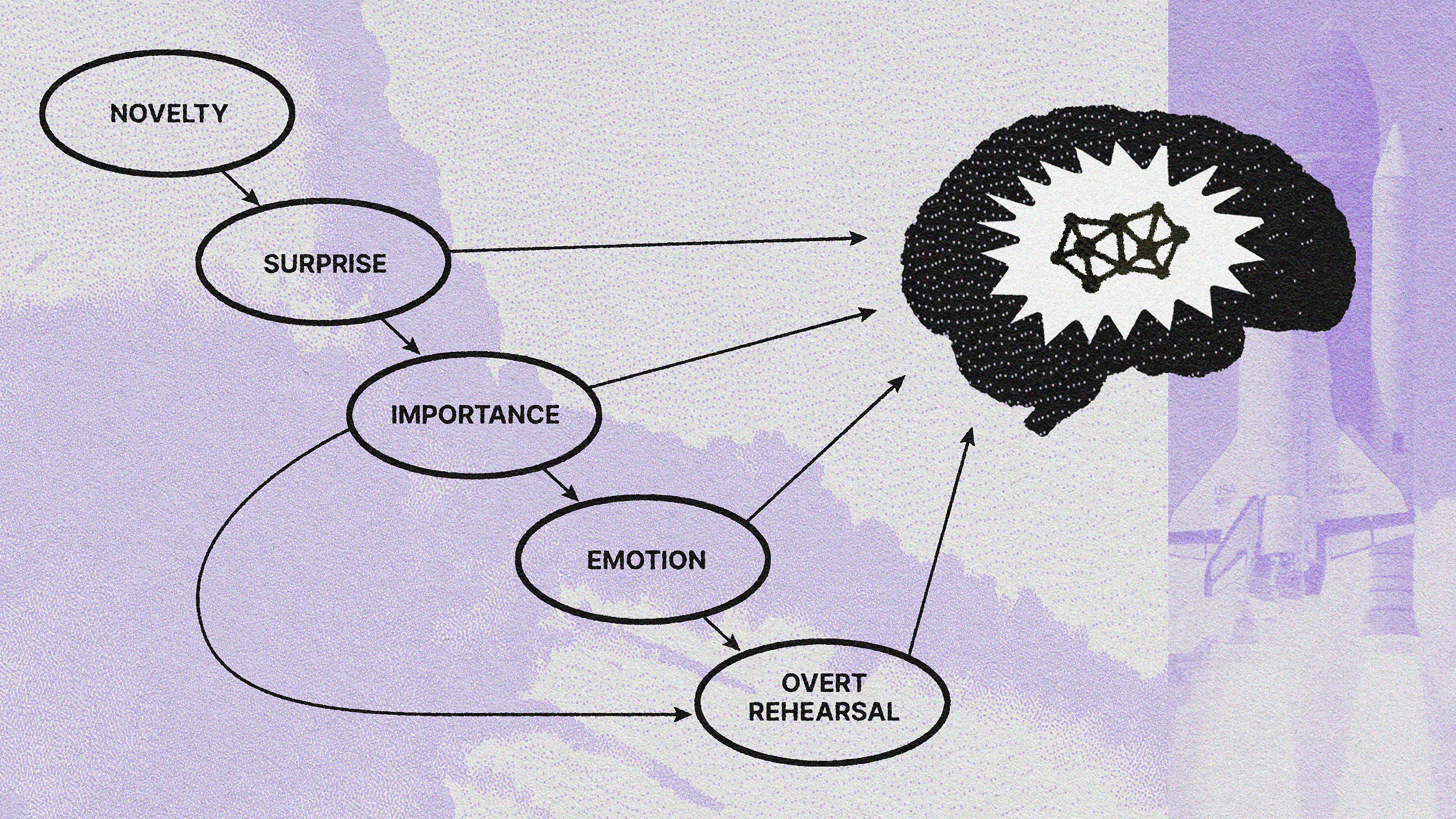

Since the psychedelic renaissance, a growing body of research has investigated the relationship between psychedelics and memory. These studies typically test encoding (how the memory is first formed), consolidation (how the memory is stored), and retrieval (how the memory is recollected).

In a 2018 study, participants viewed emotionally negative, neutral, and positive pictures. Forty-eight hours later, they were given cued recollection and recognition memory tests designed to assess recollection and familiarity with the studied pictures. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups: those who received MDMA during encoding, those who received it during retrieval, or those who did not receive MDMA at all.

The results showed that MDMA diminished the encoding of details for both positive and negative pictures, though not participants’ overall ability to recollect having viewed them. This suggests that MDMA impairs aspects of both encoding and retrieval for emotional events.

“These findings indicate that MDMA attenuates the encoding and retrieval of salient details from emotional events, consistent with the idea that its potential therapeutic effects for treating posttraumatic stress disorder are related to altering emotional memory,” the researchers wrote.

In a 2023 review of the acute effects of psychoactive drugs on emotional episodic memory (memory for emotional events), the same team wrote, “Drugs may distort memories of a prior event upon their retrieval, making them more or less emotionally charged, and these distorted memories could persist as such into sobriety.”

While there is reason to believe that psychedelics distort memories, it’s worth noting that studies testing emotional episodic memory are not the same as studies testing autobiographical memory, and may not be able to capture the same process. Still, it’s the best approach scientists have, and so far it doesn’t hold up to anecdotal accounts of recovered memories so neatly.

“Memory research doesn’t really provide evidence for the idea of recovered memories, particularly recovered trauma memories,” Manoj Doss, PhD, a research fellow at the Center for Psychedelic Research and Therapy at the University of Texas at Austin, told Big Think. “The problem with PTSD is not that people can’t remember their trauma; it’s that they can’t forget it.”

As far as the current research literature goes, Doss noted that psychoactive drugs have never been shown to enhance one’s ability to recall a prior event. Rather, people tend to report seeing stimuli that they never actually saw.

“This effect has been found with stimulants, MDMA, and THC, and I have some super preliminary data that is currently suggesting that this could happen with psilocybin,” Doss says. “All that being said, regardless of the veracity of a recovered memory, if it helps someone, that’s usually all that matters, though I do think we need to be careful when it comes to things like accusations or even delusions of grandeur in past lives.”

Fantasy or reality?

Despite his cautious attitude toward the subject, Lyon believes it is entirely possible that psychedelics can reveal hidden memories. One way in which this could occur, he theorizes, is that by disrupting the attentional system, psychedelics free up attentional resources for reallocation throughout the mind. Similar to how meditation can alter memory and attention, psychedelics could urge more memories past the threshold of accessibility and into conscious awareness. Like his colleagues, he calls for more randomized, double-blind, controlled experiments to separate fantasy from reality.

“If it turns out that the alleged memories can rarely be verified—or significantly less so than the memories revealed by other methods—then this would be a sign that psychedelics do not reveal hidden memories, and are generating fantasies instead (which may nevertheless have psychotherapeutic value),” he writes in his book.

Whatever the outcome of more rigorous studies, it’s critically important to tread as carefully as possible in this territory, lest we run the risk of invalidating survivors as we wait for the science to catch up.